Apparel brands should champion the most powerful strategies to lessen their emissions — or at least slow their rate of increase. For starters, switching to renewables across electrified supply chains would go a long way. So would abandoning wasteful fast fashion business models.

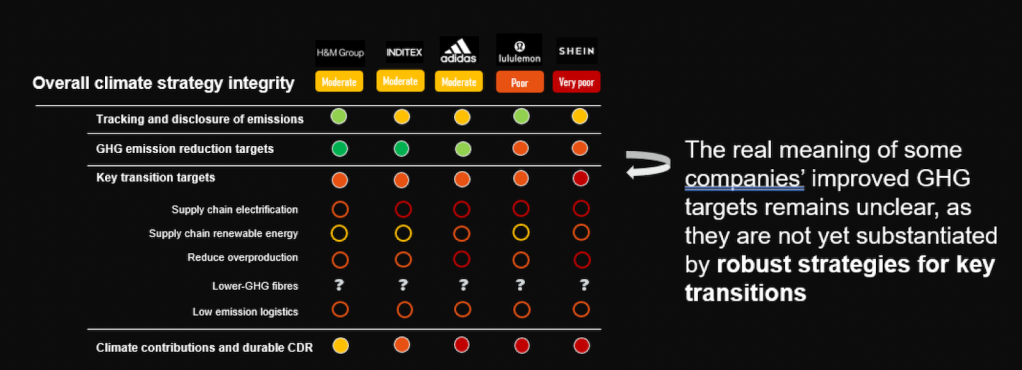

And yet major companies are mostly ignoring these proven paths, according to an analysis of Adidas, H&M Group, Inditex, Lululemon and Shein undertaken by two European nonprofits.

The New Climate Institute and Carbon Market Watch described significant improvements in fashion decarbonization and circularity over previous years in their annual “Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor,” released June 25. (The report follows parallel research about the food industry and technology giants earlier in June.) “We’re looking at much better strategies than we were three years ago for the sector, which is great,” said Thomas Day, a climate policy analyst at the New Climate Institute.

That’s the good news.

The bad: “Fundamental transitions are still missing,” Day added, citing “this exaggerated race-to-the-top dynamic that we have now for corporate claims, where companies just kind of say that everything’s fine, yet in the background might [only] be slowly ramping up their strategies.”

Exaggerated targets

The Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) has validated the net zero targets for each of the five brands. But the goals of Lululemon and Shein lack integrity, the authors found. For example, the emissions of both companies have actually surged in recent years.

And while Adidas and Inditex are also aligned with the Paris Agreement, only H&M stands out for backing up its greenhouse gas reduction targets with detailed transition plans, the report noted.

With so many corporate targets now validated by the SBTi, there’s little incentive to be a front runner. It’s also difficult to identify good practices when people perceive the standards as watered down, according to Day. “I think at this stage it’s time for a rethink, but that’s what [the SBTi is] currently in the process of doing,” he said.

Ridding supply chains of fossil fuels

Although H&M, Inditex and Lululemon set targets for renewable electricity in their supply chains by 2030, they lean too hard on Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs), researchers charged. And at apparel plants, companies too often use the “false solutions” of natural gas or biomass to replace coal.

“The key thing is to electrify those supply chains,” Day said. “Stop using coal or boilers, but also don’t just switch out coal boilers for biomass or gas — electrify processes. That’s a fundamental step to being able to use renewable energy. This is where companies need to see movement, and we’re not seeing it at all.”

H&M is the only major brand breaking down its supply chain energy mix (59 percent fossil gas, 11 percent electricity, and 3 percent each for coal and biomass). Yet even this lacks needed detail, according to the report.

Adopting circular business models

The authors advocated for business models to change not only to slow the roll of overproduction and waste, but also to transition to more low-emissions fibers across their life cycles.

Of note: H&M is the first to publish its (slim) revenue share from resale business models: from .3 percent in 2022 to .6 percent in 2023.

Day did note that more brands are providing greater detail than before, now describing exactly how and when they plan to shift to more sustainable fibers.

However, companies are generally failing to provide transparency about their progress on circularity, the report found.

Overproduction continues

Lessening production volumes is not part of any big fashion brand’s public decarbonization plan, the report found. In fact, the ultrafast model perfected by Shein is flatly incompatible with its climate goals.

“I wouldn’t necessarily expect any company to move unilaterally on this without being encouraged by regulation,” Day said. That’s starting to happen. On June 10, the French Senate voted 331 to 1 to tax low-cost clothes of high-volume brands, and to ban ads for them.

“There are some companies that make a reputation for themselves being more circular and more sustainable,” Day added. “But that’s really a niche, and for the major fashion companies, it’s not a viable approach for them unless they have a level playing field.”

Marching orders

Companies should put less emphasis on climate targets, such as slashing emissions by 50 percent by a certain year, according to Day. “There are so many ways to cook the numbers and do creative accounting to reach that 50 percent that it becomes impossible to tell companies apart,” he said.

Instead, he advised, businesses should talk less about targets and more about concrete things they’ve committed to do. Car makers, for instance, often describe their transition from fossil fuels to electricity instead of trumpeting abstract net zero deadlines.

Similarly, the fashion industry can provide tangible examples of replacing coal-powered boilers with heat batteries. And although the expenses of electrifying supply chains is seemingly prohibitive, Day observed, companies should understand that the payoff is worthwhile and “be ready to pay suppliers to pay extra to do things in a sustainable way.”

The post Report: Fashion brands are ignoring proven climate fixes appeared first on Trellis.