One of the first things Cassandra Garber saw when she arrived for her first day at General Motors last spring was a 10-foot-tall lobby-wall sign proclaiming the company’s commitment to zero emissions.

Garber had been asking herself if she had made the right move in swapping the chief sustainability officer role at Dell for the same position at GM. “And then you walk in and you see the very thing that you want to do with your entire career on a big panel on the wall,” she recalled. “You’re like, that’s mine.”

That commitment is, however, a complicated thing to inherit.

Concerns about high prices and low ranges deterred consumers from adopting EVs as quickly as the company expected when it set targets in 2021. Tailpipe emissions from new light-duty GM vehicles in the U.S. have fallen just 7 percent, likely rendering unobtainable the company’s goal of eliminating tailpipe emissions by 2035. And the Trump administration has dismantled critical regulatory support for EVs, which will further slow the transition.

Chasing Net Zero

ArcelorMittal: Inside the struggle to reach 2030 climate goals

Nestlé: On track (holes and all) for a 50 percent emissions cut

GSK: Can it keep the biggest climate promise in pharma?

Series Overview & Methodology

All of which leaves Garber with some tough decisions. Should she push back the target date? Dial back the scale of commitment? Or declare the goal itself — which depends on factors such as charging infrastructure, which GM does not control — a distraction from more impactful work?

In this latest installment of Chasing Net Zero, our series of deep-dive profiles on sustainability strategies at Salesforce, Nestlé, GSK and other large companies, we draw on interviews with Garber and outside experts to assess GM’s options.

The conversations reveal the depth of the challenge facing the new CSO, and others in similar roles. Garber has to reorient the company’s sustainability strategy amid a time of regulatory and economic upheaval, while simultaneously deciding whether to downgrade or drop what remains one of the highest-profile climate commitments from a legacy automaker.

“It’s incredibly hard for these companies to meet their climate goals, which were ambitious to say the least, in a political context that presents not just headwinds, but hurricane-level headwinds,” said Jeff Senne, a Trellis contributor and CEO of Sandbar Solutions, a corporate sustainability consultancy.

What GM committed to

Four years before Garber arrived at GM, CEO Mary Barra had unveiled a stunning aspiration: America’s largest automaker by sales, the maker of iconic brands such as Chevrolet and Cadillac, would eliminate tailpipe emissions from new vehicles by 2035. Half a decade after that, it would be carbon-neutral. The Environmental Defense Fund, which worked with the Detroit company on its vision for an all-electric future, described the move as an “extraordinary step forward.”

Those targets were extended a few months later when the Science Based Targets initiative validated GM’s goal of cutting Scope 1 and 2 emissions 72 percent by 2035. The initiative also rubber-stamped the company’s Scope 3 target: a 51 percent reduction in per-kilometer emissions from new light-duty vehicles by the same date.

Hitting those goals required a rapid transition to an all-electric future — one that then seemed more realistic. Around the time GM got SBTi approval, for example, new President Joe Biden committed to spending $170 billion on installing 500,000 EV chargers, strengthening rebates for EV purchases and other efforts to speed the transition.

Adding to the excitement around EVs was Tesla’s extraordinary rise — its stock price rose sevenfold in the 12 months preceding Barra’s January 2021 reveal, putting Elon Musk on track to become the world’s richest man — and its impact on investor expectations. Tesla’s sales growth made it the “bright shiny object,” recalls Stephanie Brinley, an auto-sector analyst at S&P Global. “If you weren’t investing in EVs and making these kind of really bold predictions, Wall Street was getting frustrated.”

What happened next

GM has since made significant achievements; its most recent sustainability disclosures, published in October 2025, note a 46 percent reduction in Scope 1 and 2 emissions since 2018, putting the company on track to hit its 2035 goal for those sources. That’s been achieved through on-site electricity generation, power purchase agreements and other mechanisms — but not by buying unbundled renewable energy certificates, a strategy that’s often criticized as having limited impact on the growth of clean power.

Yet for large automakers, the path to net zero is all about sunsetting internal-combustion cars and selling EVs. Close to two-thirds of GM’s 2024 footprint of roughly 390 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions come from the engines that power the large majority of the vehicles it sells. To hit its 2035 goals, Barra and her sustainability team needed to turbocharge uptake of the Chevrolet Bolt, all-electric Hummer and other zero-emission offerings.

Where GM’s emissions come from

Companies that aim high on sustainability are sometimes accused of prioritizing splashy commitments over detailed implementation plans. But GM’s early commitment was genuine, said a former employee involved in the target-setting process who asked not to be named because the person is not authorized to speak about their time at the company. “At GM, if you set a target, our legal staff, our controllership, everyone’s there. You can’t just set a target without a clear path of how you’re going to get there.”

Over the following five years, the company spent billions expanding its EV line-up — it now offers 12 all-electric models, more than any other major U.S. automaker — and investing heavily in new EV production facilities and battery technology.

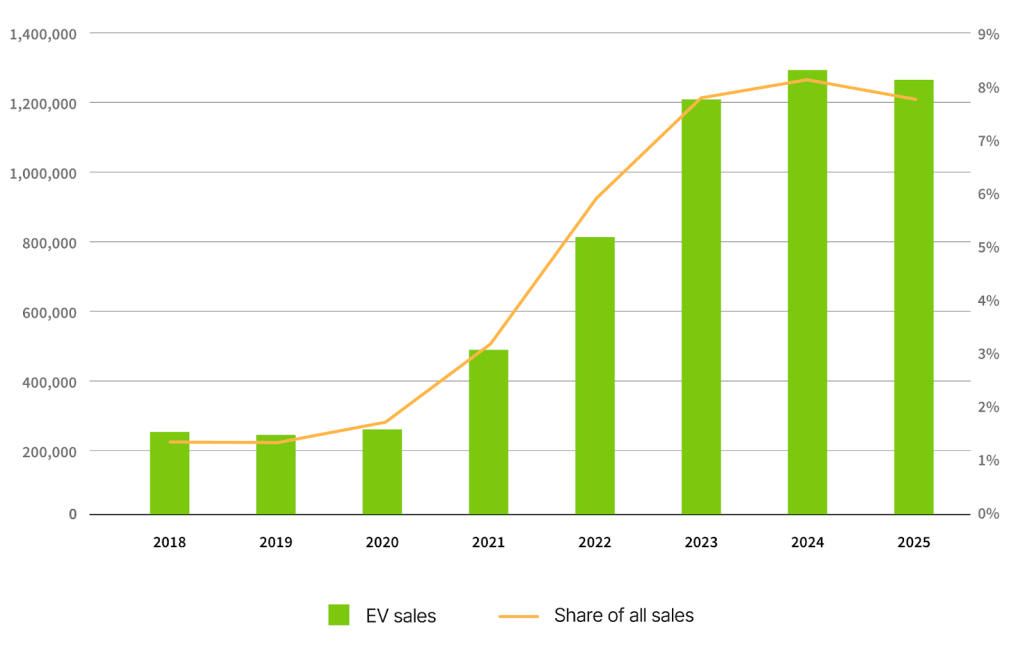

This money was still being spent when the transition spluttered. After booming in 2022 and 2023, EV sales plateaued in 2024. Cost was a major issue, said Nathan Niese, Boston Consulting Group’s global lead for electric vehicles. Sticker prices in the $30,000 to $35,000 range were mentioned, but when EVs arrived dealers asked $10,000 to $20,000 more. That ruled out mass-market buyers. Concerns about unreliable public chargers and slow charge times further hampered sales. “EV-curious people are continuing to be curious, versus actually being ready to buy,” said Niese.

Growth in U.S. EV sales has plateaued

Then, in 2025, Donald Trump’s administration cut the federal $7,500 tax rebate on EV purchases, a key pillar of the all-electric transition, helping send the market into reverse. Niese said that BCG’s latest forecasts put EV adoption in the 30-40 percent range by 2035, far short of the 100 percent GM is targeting for that date. (It’s worth noting that critics say GM’s lobbying helped kill other regulation critical to the EV transition, such as federal limits on vehicle emissions. GM says the regulations were impossible to comply with.)

All of that sapped GM leaders’ confidence in their EV roadmap. By last fall, with the rebate gone, the company was in retreat. One EV plant was retooled to produce conventional vehicles, and more than 1,700 jobs cut at EV and battery facilities. Unwinding its EV investments and contractual commitments will cost GM more than $7 billion, the company has said.

In 2025, GM sold 170,000 EVs in the U.S., just 6 percent of its total. Meanwhile, U.S. drivers have continued their love affair with gas-hungry pickups and other large vehicles. As a result, GM’s Scope 3 target is actually further away than it was in 2021: per-kilometer 2024 emissions were up 3 percent since the baseline year of 2018. The company’s 2035 deadline is still a way off, but, right now, the target Garber is tasked with hitting looks out of reach.

What should the CSO do?

Garber’s desk at GM’s offices in Warren, Michigan, is in the product department — a change for the company and one reason she took the role. “I get to sit where the emissions are,” she said during one of two phone interviews with Trellis in December and January.

In the roughly nine months since she joined, Garber has begun implementing what she calls an “enterprise approach” to sustainability. Every relevant function in the company is asked to take on a sustainability-related key performance indicator (KPI), which is developed with two key partners: a senior executive and a leader from the function who is responsible for operationalizing the KPI.

“Having KPIs and holding executives accountable across the company is game-changing when you’re trying to move the needle on sustainability,” she said.

For 2026, the product function’s KPI focuses on integrating sustainability considerations into designs for new vehicles. That could mean introducing AI features that make charging more convenient, increasing engine efficiency or reducing the number of vehicle parts to cut logistics emissions.

Elsewhere in the organization, Garber is collaborating with manufacturing on further cuts to energy use and working to add more sustainable materials to GM’s supply chain. GM is also part of the Transform: Auto program, a project with Ford, Toyota and others that helps suppliers access renewable energy.

On our calls, Garber was keen to discuss these cross-company efforts, but more guarded when the conversation turned to the status of the company’s commitments. At one point she expressed frustrations with target-setting more generally, which she described as secondary to the more meaningful work of creating lower-emission products. When pushed, she noted that the emissions goals are being reevaluated, but said there were no immediate plans to change them. What, then, are her options? Here are answers from sustainability experts who spoke with Trellis.

Option 1: Adjust the target

Several told Trellis that GM could work with SBTi to restate GM’s Scope 3 goals in a way that makes the targets easier to hit, perhaps by pushing back the target year or lowering the emissions reduction required to meet it.

Companies known for setting ambitious sustainability targets, including PepsiCo and Salesforce, have recently diluted their commitments in response to changing commercial realities. Such moves should be seen as a normal part of business, say sustainability leaders. In both cases, the restated targets retained SBTi validation and remain in line with the goal of limiting global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming.

“Companies get some negative headlines, some ‘tsks’ and a little bit of scolding,” said Steve Rochlin, a Trellis contributor and CEO of Impact ROI, a corporate sustainability consultancy. “However, companies can manage it by saying we’re not moving away from our long-term goals.” One critical factor, he added, would be whether the company’s long-term goal remains intact. In GM’s case, Barra has said that while the company’s path will change, the destination is still zero emissions.

The cost of downgrading goals is also lower now due to the weak job market, added one leader with decades of sustainability experience, who requested anonymity because the consultancy they work for has a relationship with GM. The biggest audience for annual sustainability reports is often prospective employees, the consultant noted. With bigger pools of applicants to choose from, the pressure for a company to advertise its climate bona fides has lessened.

Option 2: Stay quiet

The argument for restating would likely be conventional wisdom in a normal business environment — but we’re not in one. Companies are operating in a world where one Republican state attorney general has accused the SBTi and CDP of being part of a “climate cartel,” and others have banded together to attack the use of renewable energy certificates by Google and other tech giants. One consequence of these attacks — in fact, perhaps one goal of them — is to deter companies from making any kind of announcement about sustainability.

With that in mind, Garber could conceivably decide to say nothing about GM’s targets, at least until the political climate shifts. “Some companies know they’re not going to meet their target, but they’re like, “Yeah, we’re not even going to go change it, because we don’t even want to generate a conversation about it, we’re just going to keep doing what we’re doing,” said the consultant.

Option 3: Break ties with SBTi

A third option would be to set a new target outside of the SBTi process. Garber did not suggest doing so, and parting ways with one of the most influential standard-setters would risk undermining ambition across the autosector. But there’s no doubt it would provide GM with flexibility on several issues, including one that concerns Garber: the sync between targets and business planning.

“You should create your goals against the same timelines as your business,” she said. “Because that’s how sustainability gets integrated.” The deadline for GM’s SBTi goal was 14 years in the future when it was set; automotive planning, noted Garber, tends to look five years ahead.

Opting out of the SBTi process would also allow GM to leverage other strategies, including the use of carbon credits. Take Microsoft, for example. The company left the SBTi’s net-zero process in 2024. Its headline climate goal — going carbon negative by 2030 — now relies on plowing billions of dollars into carbon credit projects.

The year ahead

Garber did not appear to be in a rush to decide between these options, but she will have to say something soon. SBTi rules require companies to review their targets every five years. After the end of April, GM will have six months to submit its review to the organization. If an update is required, the company will have an additional six months to finalize changes.

SBTi rules are not the only reason why GM might clarify its intentions. GM’s record on climate is viewed as mixed by some environmental groups, in part because the company has lobbied against pro-climate legislation. But even though the 2035 deadline for CEO Barra’s pioneering commitment will likely be missed, she is praised for introducing a goal that served as a north star for the company’s sustainability efforts. “In some respects that was more important than the year,” said S&P’s Brinley.

Looked at from that perspective, Garber’s best course may be to choose the least bad of the options available — and to do so quickly. Then she can get to what sustainability professionals would say is the real and more daunting challenge: uniting the company — which employs 155,000 people around the world — in an effort to hit those new targets.

Cassandra Garber will speak on the mainstage at GreenBiz 26 later this month. GM is also a sponsor of the event.

The post GM’s pioneering emissions goal looks out of reach. What can it do? appeared first on Trellis.