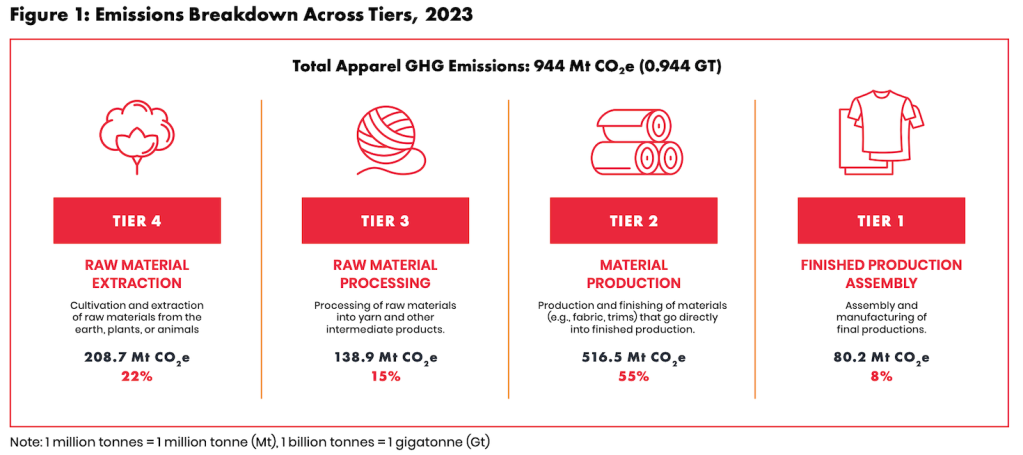

The sewing room may be the most visible symbol of manufacturing in fashion. The work of assembling finished products, known as Tier 1 in the supply chain, is also increasingly accounted for in sustainability reporting.

But it’s the Tier 2 facilities — the ones that produce, dye and finish fabrics and trims — that actually create more emissions.

Renewable energy only makes up 2 percent of energy use across both Tier 1 and Tier 2. But while Tier 1 makes up about 9 percent of supply chain emissions, Tier 2 produces more than 50 percent.

Finding climate emissions hotspots across those energy-intensive facilities can go a long way toward helping the fashion industry decarbonize, according to Joel Mertens, director of Higg Product Tools at Cascale, formerly known as the Sustainable Apparel Coalition.

“A company’s sphere of influence starts to enlarge,” he said.

Data emerges

Cascale analyzed patterns from data from thousands of Tier 1 and 2 facilities, reported in 2023 and 2024 by brands and retailers through its Higg Index. The results appeared in Cascale’s State of the Industry Report on Jan. 28.

Tier 2 processes make up between 45 percent to 70 percent of brands’ Scope 3 emissions, according to a McKinsey analysis in March 2025 of data from more than 9,000 suppliers. McKinsey suggested two decarbonization “levers” for Tier 2, including brands favoring low-emissions suppliers. The consulting giant also suggested that suppliers make technical adjustments, such as adopting renewable energy.

However, the special challenges of Tier 2 include a heavy reliance on boilers for dyeing, finishing and drying material. Coal makes up 31 percent of the industry’s energy sources overall, and 40 percent within Tier 2, according to Cascale.

“Thermal energy is harder to decarbonize than electricity,” said Mertens. “If you have a boiler, it doesn’t really change until you change that boiler.”

One alternative includes brick batteries, which H&M is exploring for its mills. In 2024, the brand’s Green Fashion Initiative backed Tier 2 suppliers in Vietnam and India that were installing biomass boilers.

Another challenge for Tier 2 reduction hopes: Its geographically scattered facilities are often larger than Tier 1 cut-and-sew shops. Emissions tend to be concentrated in a small number of large suppliers, Cascale found.

“The larger facilities tend to have more equipment and processes, higher energy needs and show a higher carbon intensity in general,” Mertens said. “Because emissions are concentrated in a small number of suppliers, it’s actually an opportunity. We can target our conversations to a smaller subset of manufacturers, where the interventions are really going to make a difference.”

The counterpoint to that, however, is that change requires collective action, he added.

To that end, the Outdoor Industry Association runs a Clean Heat Impact CoLab. Under that effort, Patagonia, L.L. Bean, Cotopaxi and other outdoor labels created an open-source Textile Heating Electrification Tool one year ago for mills to adopt.

Where the action is

Meanwhile, the nonprofit Apparel Impact Institute (AII) is addressing funding bottlenecks that Cascale identified as inhibiting progress. On Jan. 27, the AII realigned its Climate Solutions Portfolio, which provides grants of up to $250,000 for decarbonization solutions, to emphasize supplier-focused electrification efforts, especially in Tier 2 plants. It belongs to the organization’s Fashion Climate Fund, built to mobilize $250 million toward $2 billion in blended capital for low-carbon supply-chain adjustments.

“We see brands starting to plan their longer-term electrification strategies by country and supporting suppliers with technical and financial assistance to do so,” said Pauline Op de Beeck, the AII’s climate portfolio director. Brands are also increasingly sharing what they’ve learned from pilot projects, she added.

And support for Tier 2 climate-transition work by suppliers has continued under the Future Supplier Initiative, a collective financing model engaging the Fashion Pact and the AII with Guidehouse and DBS Bank. Marks & Spencer, Ralph Lauren and Tchibo joined in 2025 alongside the original member brands Bestseller, Gap Inc., H&M Group and Mango.

In November, 55 CEOs, including from luxury houses Chanel and Prada Group, committed to the Paris-based Fashion Pact’s European Accelerator. Joined by Kering, Moncler Group and others, the collaboration seeks to drive decarbonization deeper into their upstream supply chains.

Other work to advance low-emissions technologies among fashion suppliers include Cascale’s Manufacturer Carbon Program. It helps brands measure emissions at plants and encourages them to assist suppliers with decarbonization projects.

Meanwhile, Schneider Electric has recently teamed up with Levi’s and Marks & Spencer in separate efforts to help the companies’ mills and dye houses access renewable energy through power purchasing agreements.

“There isn’t one model that’s risen to the forefront and said, ‘This is the solution,’” Mertens said. “The only way we get there is by having some uncomfortable conversations across the value chain.”

The post The real carbon hotspots in fashion aren’t where brands look first appeared first on Trellis.